Print

Print

Taylor Swift has a stalker problem. In April 2018, a man broke into her New York City loft and took a shower before falling asleep in her residence.The same stalker attempted to break Taylor Swift’s front door down with shovel in February 2018. Other stalkers have sent emails threatening to kill Taylor Swift’s entire family. Suffice to say, Taylor Swift and other public personalities should take all reasonable steps to protect themselves and their families. And, thankfully, it appears Taylor Swift is taking these threats seriously. In addition to taking a variety of other security measures, a number of news reports indicate Taylor Swift has installed a face-recognition camera at her concerts that cross-references pictures of her known stalkers.

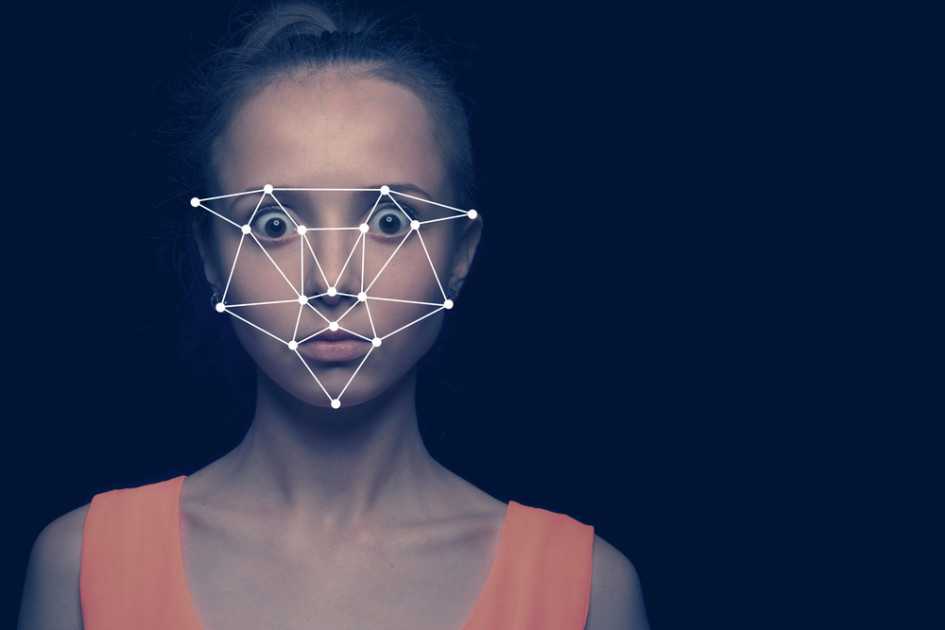

Taylor Swift fans mesmerized by rehearsal clips on a kiosk at her May 18th Rose Bowl show were unaware of one crucial detail: A facial-recognition camera inside the display was taking their photos. The images were being transferred to a Nashville “command post,” where they were cross-referenced with a database of hundreds of the pop star’s known stalkers, according to Mike Downing, chief security officer of Oak View Group, an advisory board for concert venues including Madison Square Garden and the Forum in L.A. “Everybody who went by would stop and stare at it, and the software would start working,” says Downing, who attended the concert to witness a demo of the system as a guest of the company that manufactures the kiosks.

While there is no reasonable argument against Taylor Swift taking reasonable steps to protect herself from stalkers, we cannot ignore the privacy questions related to this new security method. Specifically, there are significant questions involving the privacy of individuals that have their images captured, the vast majority are not stalkers. And, unfortunately, there is little guidance on how this new technology should be used.

While we do not have substantial legal guidance on this new security method using biometric data, there are at least a couple of sources that provide some insight. At present, most protections for biometric data arises out of state laws and regulations such as the Illinois Biometric Information Protection Act (“BIPA”). BIPA states that “[a]ny person aggrieved by a violation of this Act shall have a right of action in a State circuit court or as a supplemental claim in federal district court against an offending party.” As it stands, the technology that allows for the storage and collection of biometric data may be outpacing the development of protections for this information. For example, by using the term “aggrieved,” there is a possible violation under at least one or any of the following scenarios:

- The collection of biometric data without the individual’s consent;

- The collection and use of biometric data without the individual’s consent;

- The collection of biometric data with consent but use without consent;

- The collection of biometric data with consent and use of the data outside the limited consent provided by the individual.

While BIPA clearly states any person “aggrieved by a violation” of BIPA has a potential cause of action, there is little guidance as to when a person should bring suit.

While the protections arising from BIPA are cutting edge compared to most states where there are no protections in place for biometric data, courts are still being called upon to interpret biometric data protection laws. For example, the Illinois Supreme Court recently heard arguments in a case that may become the cornerstone decision interpreting the term “aggrieved” as used in BIPA.

In Rosenbach v. Six Flags Entertainment Corp., 2017 Ill. App (2d) 170317, 2017 WL 65239, the Illinois Court of Appeals held allegations that an amusement park taking patrons’ thumbprints without proper consent was not a violation of the Act because the patrons were not aggrieved under the Act. The Defendant, Six Flags Entertainment Corporation (“Six Flags”), operates an amusement park located in Gurnee, Illinois. The Plaintiff, Stacy Rosenbach (“Rosenbach”), is a parent of a 14-year-old boy that visited Six Flag’s amusement park for his class trip. Before the trip, Rosenbach purchased a season pass for her son using Six Flag’s website. Rosenbach claims she was surprised to find out that her son was directed to scan his thumbprint to gain access to Six Flags and to receive his season pass card. Rosenbach claims she would not have purchased the season pass for her son if she knew Six Flags intended to collect his thumbprint without obtaining written consent or disclosing their plan to collect such data.

In determining whether real or actual harm was required for a party to be “aggrieved” under the Act, the Court of Appeals held “if the Illinois legislature intended to allow for a private cause of action for every technical violation of the Act, it could have omitted the word “aggrieved” and stated that every violation was actionable.” Based on this reasoning, the Court of Appeals held Rosenbach could not recover because “a plaintiff who alleges only a technical violation of the statute without alleging some injury or adverse effect is not an aggrieved person” under the Act.

Of course, data collectors and individuals will have more guidance once the Illinois Supreme Court either affirms or reverses the Court of Appeals in Rosenbach. And, while the Supreme Court will provide some clarity, we should not be surprised if this decision fails to answer all questions related to BIPA.

The privacy issues are clear even when viewed outside of the various biometric data laws. For example, the Rolling Stone article on Taylor Swift’s use of the images asks: “Despite the obvious privacy concerns — for starters, who owns those pictures of concertgoers and how long can they be kept on file?” And, that is a reasonable question for any data collector or individual having their data collected. In addition to the concerns discussed in Rolling Stone, there are a number of other questions that quickly come to mind: Can Taylor Swift keep the images and cross-reference them down the road when new stalking cases arise? Are the images limited to be used in only stalking cases? Can Taylor Swift use the images for marketing purposes? Do concertgoers need to give consent to have their images taken? In simpler terms, Taylor Swift’s security team will need to analyze the likelihood that non-stalker concert-goers are going to be “aggrieved” by having their photos taken without consent. Suffice it to say, the parent in Rosenbach may be just as angry if she sent her teenager to a Taylor Swift concert and her child was photographed without consent. Consequently, even though courts are increasingly providing clarification on these issues, we can expect to see technology continue to outpace the law on biometric issues.